Campfire Classics

Notes on the book

by Maurice A. Williams

|

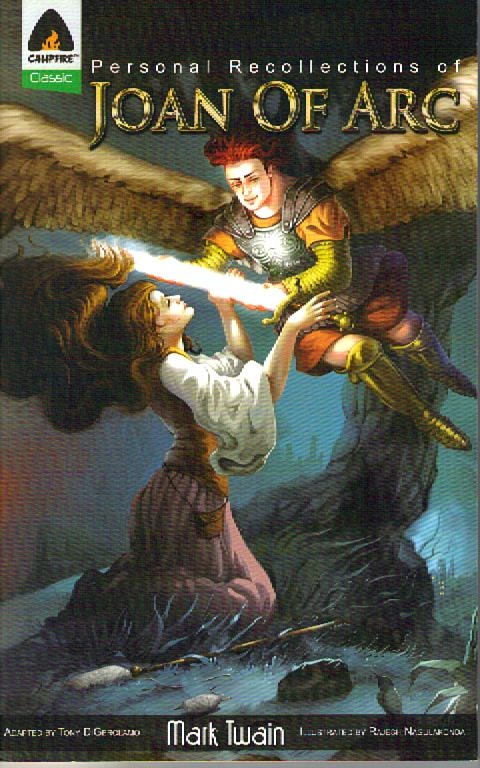

PERSONAL RECOLLECTIONS OF JOAN OF ARC

Campfire Classics

|

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Mark Twain

Adapted by Tony DiGerolando

c. 2010

ISBN: 978-93-80028-43-9

Campfire Classic Novels

Kalyani Navyug Media Pvt. Ltd

New Deli, India

www.campfire.co.in

68 pages, $9.98

Here is what their Website says about their mission: "To entertain and educate young minds by creating unique illustrated books to recount stories of human values, to arouse curiosity in the world around us, and to inspire by tales of great deeds of unforgettable people."

Page and Remarks06 The Fairie tree. [Historical! This tree the “L’Arbre Fee de Boulemont” (a tree where fairies gather)

features in Joan’s trial because her enemies wanted to use it to convict her of attributing to this tree powers that

belong only to God. Here is what Joan said in her trial: [“Quite close to the town of Domremy, there is a tree called

The Ladies’ tree, and others call it the Fairies’ tree, near which there is a spring of water, and I have heard tell that those

who are sick and have the fever drink the water of this spring and ask for the waters to recover their health. I have

witnessed this myself but I do not know if it cures or not . . . Sometimes I went out with the other girls and by the tree

made garlands (flowers) for the image of Our Lady of Domremy . . . I do not know whether, since I reached the age of

discretion (l’age de raison), I ever danced about the tree; I may have danced there with the children but I sang there

more than I danced. (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 21-22)]” and when Joan was questioned again: “Know

you ought of those who go wandering with the fairies?” She said: “I have never been there and I know nothing else

about it; but I have indeed heard it said that they went on Thursdays; but in that I do not believe and I believe that

there is nothing in it unless it be witchcraft.” (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 178]). And here is what Mark

Twain had Joan say to Father Fronte in his book: “Joan you were used to make wreaths there at the Fairy tree with

the other children; is it not so?” “Yes. Father.” “Did you hang them on the tree?” No, Father.” “Why didn’t

you?” “I—well, I didn’t wish to.” “Didn’t wish to?” “No, Father.” “What did you do with them?” “I hung them

in the church.” “Why didn’t you want to hang them on the tree?” “Because it was said that the fairies were of kin

to the Fiend, and that it was sinful to show them honor.” “Did you believe it was wrong to honor them so?” “Yes, I

thought it must be wrong” (Mark Twain, Historical Romances, p. 567).

Campfire Classic has: “All children brought up in Domremy were called “The children of the Tree”. This tree is sacred

because, when a child of the tree is about to die, a vision of the tree comes to him. If the child has been a sinner, then

the tree will appear cold and lifeless, but if the tree appears full of life, then the child is pure of heart, and will go to

heaven. However, Twain did not write this, and it is not supported by Pernoud. So, perhaps, this is one reason why

so many critics claim Twains’ Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc is fiction; one critic even cites Twains emphasis

on fairies, prophecies, and miracles.

08 The parish priest denounced the fairies as evil and exorcised the tree.

09 Father Fronte, because a woman saw the fairies at night when the children were sleeping, went to exorcise the tree again and banished the fairies. (This episode with exorcising the tree seems to be fictional, but the tree did exist and the children did play around it (see above). And Domremy’s parish priest was named Pere Guillaume Front (Pernoud, Her Story, p. 17). Joan was sick at the time, but, when she recovered, she went to Father Fronte. She reminded him that he had told them they would have to go if they showed themselves to the children again. She points out that did not show themselves to the children. They came at night when the children were in bed.

10 “If a man come prying into a woman’s room at midnight when she is naked, would you say that the woman is guilty of showing herself to the man?” “What is your heart made of if you can pity a Christian’s child, but not the devil’s child? The devil’s child needs your pity far more.” This whole conversation with Father Fronte is fictional, and Mark Twain did not write the conversation as it appears in this Campfire Classics book. Twain does have Joan tell the priest that she thought it sinful to show the fairies honor. This is true as was shown in (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 178).

11 A homeless stranger came to Joan’s home. Joan gave him food against her father’s objections. There is a similar historical episode about Joan (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 18).

12 Edward Aubrey defended Joan’s actions, Twain has this fictional person be Edmund’s father the mayor of Domremy, but there is no historical evidence that this conversation occurred.

13 Mention of the Hundred Years War and the Song of Roland.

14 A treaty signed between the King of England and the Queen of France, and an explanation of “Dauphin.”

15 A man named Benoist came out of the woods.

16 Joan led him back to his cage.

17 In 1428, the Bungundians attacked the village. Joan led the people away to safety. They returned a few days later to see the village destroyed.

18 Benoist lay in his caged killed by the Bungundians. This episode about Benoist appears to be fictional. I found no historical information about Theophile Benoist in Pernoud.

19 Joan tells Louis and Aubrey of the battle of Agincourt and that she will lead France to victory within two years.

20 Louis comes upon Joan while she is having a vision.

21 Joan tells Louis about her messages.

22. Louis (along with Joan’s Uncle Laxart) takes Joan to the governor of Vaucouleurs.

23 Joan asks the governor, Robert de Baudricourt, to send her to the Dauphin.

24 Robert says “Take her home and whip her soundly” [True (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 33)].

25 Two of the governor’s men come to laugh at Joan, but believed her and gave her their swords. The governor came again to see if she were a saint or a witch. Joan tells him “a battle was lost today”.

26 It takes nine days for news from Orleans to reach Vaucouleurs. In the meantime Joan’s fame spreads among the people. They equip her with soldiers clothing and give her a horse and teach her how to ride it. The governor gets word of the battle and believes Joan.

27 The governor decides to provide Joan with escort to see the Dauphin [True (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 34), but the men, Jean de Metz and a companion, volunteered themselves to accompany her].

28 The next morning, he appoints some men to accompany Joan.

29 On the way, one of the men plots Joan’s death. She tells him: “It’s a pity that you plot another’s death, when your own is so close at hand.” The next morning the ringleader’s horse pinned him under water while we (the narrator) were crossing a river. He drowned before we could help him.” Mark Twain does have this scene in his book, and two of the movies about Joan of Arc also have something similar to it, but I could not find historical confirmation that it is true.

30 They stop at Gien, nineteen miles from Chinon, where the Dauphin is. Joan’s fame spreads. Joan dictates a letter to the Dauphin at Chinon.

31 The Dauphin’s mother-in-law, Queen Yolande of Sicily, advises the Dauphin to see Joan. His political advisors advise him to send them instead. Joan tells them her message is for the Dauphin only.

32 The Dauphin agrees to see Joan. He believes her.

33 He makes Joan general-in-chief of the armies of France.

34 Joan dictates a letter of warning to the English commander at Orleans advising him to abandon their strongholds and return to England. Joan’s voices told her to fetch a sword hidden behind the altar of St. Catherine’s church at Fierbois. The sword belonged to Charlemagne. Mark Twain did write about this, and it is true (Pernoud, Her Story, p. 16).

35 Joan needed more troops. She sends La Hire to bring them from Blois. She wanted the troops to confess their sins and attend daily Mass. She asked La Hire to refrain from using God’s name in vain. This book says La Hire is an atheist. Mark Twain did not say that. The prayer attributed to La Hire was cited by Twain and is historically correct (Pernoud, Her Story, p. 188).

37 Joan rescues “the Dwarf” who had deserted from the army. The Dwarf is a fictional character that Twain introduces into his book.

38 Joan’s generals were cautious about attacking Orleans, but Joan insisted they must do it.

40 Joan had her army attack the English who had retreated into a fortress. Joan’s army captures the fortress in three hours. Orleans was free! [Actually there were several battles].

41 Joan comforts a dying soldier. Joan then wiped out all the nearby English strongholds. At the battle of the Bastille of Augustins, her army wavered for the first time, but Joan did not waver. She shouts “If there are just a dozen of you who are not cowards, it is enough! Follow me! [I think this is true, but, at the moment, I can’t find historical documentation. Victor Fleming had Joan saying this in his movie Joan of Arc].

42 When her soldiers, who had retreated, saw Joan sending the enemy scrambling, their courage returned. They captured the Bastille in one hour. In just seven months, Joan had conquered Orleans and the surrounding regions. By May 8, 1429, the English commander, Talbot, was forced to flee the region.

43 There was one more English fort to take. Joan’s army won the battle, but Joan was injured [True (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 90)]. Joan encourage the Dauphin to travel to Rheims to be crowned King. He wasn’t sure it was safe.

44 The Dauphin made Joan and her family nobles, but because of the Dauphin’s indecision, the army began to disband. Joan and her generals raise a new army.

45 The first day along the Loire River, they took the fortress at Jargeau. Talbot retreated from his garrison at Beaugency and left some men to defend it. They surrendered to Joan.

46 Joan attacked Talbot in his garrison at Menge, but he had evacuated the garrison. The French had won three great victories so far.

47 On the fields of Patay, Talbot had positioned his army in an open field. The English were good at fighting in the open field. The French general d’Alencon was saved from death by a warning from Joan [True (Pernoud Her Story, p. 57 & 59)].

48 Joan defeats Talbot and takes him prisoner.

49 Joan rescues an English soldier who was mortally wounded. She comforts him and sends for a priest to help him [True (I think this is historical, but, at the moment, I can’t find documentation)].

51 The Dauphin finally went to Rheims, where he is crowned King. The King tells Joan to ask for anything she wants. She says her work is done and she would like to go back home and she asks that Domremy become exempt of taxation. Domremy did not pay taxes for 360 years after that [I’m sure this is true, but forgot where the reference is].

52 The King made Joan ride with him through the city streets so the people could see her. She saw her father and uncle. The King was gracious to her father and uncle.

53 Joan planned to return to Domremy with her father and uncle, but the King asked her to remain with him. The King’s advisers cautioned him that it would be foolish to try to liberate Paris.

54 Finally, the King agreed to send Joan to liberate Paris, but his advisors later convinced him that this was a mistake.

55 Joan sent a message to the King begging him to allow her to march into Paris, but the king said “no!” Joan fought her last battle in Compiegne [Actually, Joan liberated Compiegne on August 18, 1429. From Compiegne, Joan gave the command to march against Paris. Her troops conquered several cities surrounding Paris and finally St. Horore, where she was wounded. The French king at that time forbade any further assaults and disbanded the army. Compiegne then fell back under siege by the English. Nine months later, in May 1430, Joan decided to lift the siege, and that was when she was captured].

57 Joan is captured. She escapes prison, but is soon recaptured.

58 She is taken to a stronger prison, and tries to escape again. She is injured [True (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 154)]. The English and Burgundians wanted Joan dead, but if they simply killed her, she would become a martyr. So they got the French bishop Pierre Cauchon of Beauvais to prove that Joan is a puppet of Satan and have her condemned for witchcraft. In return he was promised the position of Archbishop.

59 Joan was taken to Rouen, occupied by the English and Burgundians. Noel Rainguesson, a fictional character, shows up where Louis de Conte, also a fictional character. They decide to do whatever they can to help Joan. They go to Rouen. Louis finds employment as a recorder at the trial. These fictional characters are a means for Mark Twain to introduce himself into the story of Joan.

60 Cauchon tried to convict Joan with her own testimony, but she was too smart for him. He decided to start a second trial.

61 The second trial also did not convict Joan. Cauchon decided on a third trial.

62 Cauchon waited for weeks while he deprived Joan of sleep, of religious articles, and even listened in while Joan confessed to a priest posing as her friend so that Cauchon could her secret concerns against her [True (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 172)]. Then Cauchon appointed a new judge and started yet another trial.

63 It did Cauchon no good. The trial was also deadlocked. Louis dreamed that the King would rescue Joan, but the reality was that the King was not coming.

64 After six deadlocked trials, Cauchon did something shameful. He took Joan out by the stake where she will be burned and told her she must abjure or be burned. Joan was frightened, and she did not know what “abjure” means, so she signed the abjuration document [True (Pernoud Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 216)].

65 Once the document was signed, Cauchon said “Burn the witch!” Joan is tied to the stake.

66 The fire is lit. As the fire burns, Joan sings a song to the fairie tree. Her last words before she died were “I die not through God, but through you,” and she dies.

67 Louis de Conte recalls that not a day has gone by that he does not remember Joan. He remembered her telling the King that if he did not attack Paris, it would take him twenty years to free France. Twenty years after her death, her prediction came true. France was finally free. The king, much older and wiser, remembered Joan. He arranged for a new trial in front of the Pope, and her good name was restored. Louis thinks Joan went straight to heaven. While Louis is thinking these thoughts, he is sitting next to the fairie tree.

68 When Joan’s father heard of her death, it broke his heart and he passed away. Joan’s mother was granted a pension by the city of Orleans. The fictional Noel and Louis returned to the Kings service. La Hire and Dunois lived to see France’s freedom. The last page shows Joan being accepted by her father in heaven and La Hire and Dunois souls approaching Joan. The very last image is, once again, the fairie tree. Mark Twain did not write about Joan being accepted by her father in heaven or make any reference to the fairie tree at the end of his book

All in all, the Campfire Classic book follows the storyline in Mark Twain’s original book pretty well, much better than all four of the movies I saw about Joan of Arc. The movies condense all of Joan’s military campaigns into two or three composite battles, which do not show her military career as it really was.

Even worse, three of the four movies seriously distort her personal life and show her disrespectful somewhat arrogant toward persons she was bound to show respect to. The only movie that showed Joan’s personality pretty much as it really was is Victor Fleming’s Joan of Arc. None of the movies amplified the role of fairies and the fairie tree as this Campfire Classic does.

This is the only real flaw I see in the Campfire Classic book. It might seem harmless to attribute more to the fairies than Mark Twain did, or even more than Joan of Arc did, especially today when there is widespread interest in otherworldly beings: witches, aliens, people with paranormal powers, etc., but in Joan’s lifetime, attributing powers to these being would have been considered witchcraft. If her enemies could have proven that Joan actually did do this thing, they would have had an easy time of having her convicted of consorting with evil spirits. As it turns out Joan did not think doing this was right, and Mark Twain knew she did not, and his story of Joan of Arc shows that she did not.

If you found this Campfire Classic interesting and would like to know the full story of Joan’s life and military career presented in an interesting and easy-to-read biography, you cannot do better that read Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc. It is to Mark Twain’s credit that he adhered so closely to the historical record when he wrote his book. He did add some fictional characters and episodes, but they did not contradict what the historical record had to say about Joan of Arc and her career.

Maurice A. Williams

Bibliography:

Joan of Arc: By Herself and Her Witnesses, 1990, Regine Pernoud (Author)

Joan of Arc: Her Story, 1999, Regine Pernoud, Marie-Veronique Clin (Authors), Jeremy duQuesnay (Translator)